[ad_1]

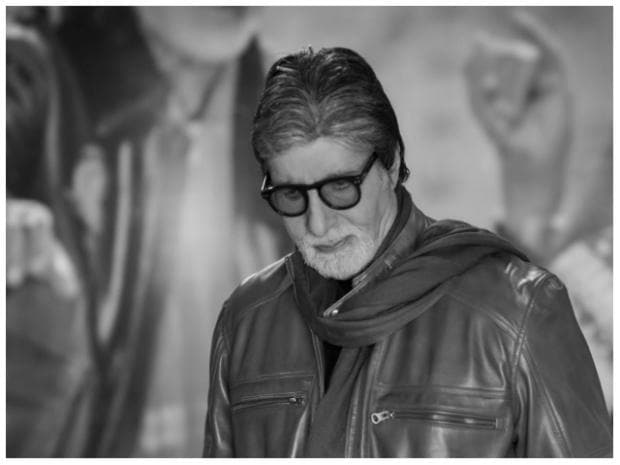

In 1978, when Amitabh Bachchan’s Don first came to cinema theatres, Saharsa was a tranquil little town at the heart of Bihar’s Mithila region, known for the creaminess of its milk, succulence of its sweets, and mellifluousness of Maithili, the local dialect. The majority of Saharsa’s population, not more than a few thousand, was engaged in agriculture, government jobs, and small trading.

In 2022, as PVR brought Don back in theatres, Saharsa is not much different from how it was in 1978. It is still small and marred by illiteracy and poverty. A few things have changed, though. The silent rolling of e-rikshaws has elbowed out the tinkling of cycle rikshaws, there is a raft of boards announcing sale and service of mobile phones, and many green patches have got covered by garbage, mainly polythene bags. The population has grown, of course, though hemmed in by the exodus of those seeking better careers elsewhere – such as this writer.

And yes, Saharsa’s three cinema theatres have lost their pride of place in the lives of its residents.

When Don first released, Saharsa’s theatres were the heartbeat of the town. Prashant Chitralaya was a stone’s throw from the terminus that flagged off overnight buses showing Hindi movies on a video screen and bound for Patna. It was the grand one – large, with seats that sometimes managed to slide – and proudly advertised its “air-cooled” status.

Meera Talkies was the snooty one: it won’t give free passes to families of government officers.

And Ashok Talkies, mired in legal cases, showed random movies whenever it opened for shows – which would be once every few months.

Maar dhaad boxingbaazi

Actually, all three screened random movies, or movies which became random by the time they came to Saharsa. In the era of single-screen theatres, movies started screening in the prime territories of Delhi and Mumbai before fanning out to the smaller centres. It took a year or so, sometimes more, by for a “new release” to reach places such as Saharsa.

But when they did, the successful ones created a celebratory atmosphere that permeated through theatre walls and fanned out, enveloping the little market around the railway crossing that divided the city and reached as far as the mohallas (the old settlements) as well as the colonies (the new ones, mostly government housing).

Every morning, two cycle rickshaws laden with loudspeakers and covered in posters – one for Prashant and the other for Meera (Ashok had little to announce) – wound their way through the streets announcing the film each theatre was showing. Curiously, every film was described by the announcer as “maar dhaad aur boxingbaazi se bhari hui mahaan samajik film (a great social packed with fights).”

The movies became the topics of discussion during evening gatherings of neighbours and work colleagues. With no television, no internet, and a bevy of children to keep engaged, families visited one another every evening and colleagues became family friends. The children played together, the men drank copious amounts of tea, and the women scurried around looking busy – which they always were.

The successful movies drew repeat audiences in hordes. Some “successful” ones would come as a surprise to the metro dwellers. Movies such as Nadiya Ke Paar (A Rajshri offering later remade as Hum Aapke Hain Kaun) and Sanam Bewafa (starring Salman Khan) ran for weeks, perhaps months. Mother India, already an old classic, packed the theatres every time it re-released. The odd Bhojpuri movie did well, too, the most notable being Ganga Kinare Mora Gaon.

Once inside the theatres, you followed a strict segregation. Officers’ families, who did not need to buy tickets, sat in a what was called a “box”, a special oval section with about a dozen or so seats. Their entry was through passes issued by the manager and they were often supplied with soft drinks and snacks on the house. The second stratum was Dress Circle, whose tickets were the priciest, followed by the Balcony. The rest – the hoi polloi – sat in the Upper Stall and Front Stall, both of which were on the ground level.

It was the hoi polloi who seemed to have the most fun. Armed with cheap tickets, they thronged their favourite movies over and over, and often recited the thunderous dialogues along with the characters on the screen. They whistled and hooted and catcalled at the paisa wasool moments, and threw coins on the screen if they liked a song. The young and the restless would sometimes get up and dance in the aisles. Some of them brought flashlights even for the day shows and, during the inevitable power failure, switched them on and pointed them at the blank screen while everyone else jeered for the generator to start.

Saharsa’s spirit rekindled in Gurgaon

All of this was on full display at a multiplex in Gurgaon, where Don was being screened to mark Bachchan’s 80th birthday celebrations. The screening was part of ‘Bachchan: Back To The Beginning’, a retrospective of 11 films in 19 cities organised by the Film Heritage Foundation and PVR. But it was not the hoi polloi of Saharsa but the hoity-toity swish set of the Millennium City that was doing the whistling and hooting and dancing and the dialogue baazi.

It started right in the opening scene, as Bachchan emerged from the car he had just driven through an open field, and was now facing three men holding guns pointed straight at him. Chants of “Bachchan, Bachchan” rent the air-conditioned air of the auditorium. And so it continued from there on.

Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, the duo that wrote the screenplay, would be delighted to hear the cheering that erupted when their names flashed in the credit sequence. As the story goes, when Zanjeer’s posters in 1973 did not mention their names, the two hired a painter to write, “written by Salim-Javed”, on the posters all over Mumbai.

The audience wasn’t just made up of the people who were young when Don first released in 1978. It was a mixture of age groups. Some of them looked young enough to be watching it on the big screen for the first time, and they showed their appreciation with unflagging enthusiasm. There was no power failure, but there were moments when the audience did not find the volume to be loud enough and shouted for raising it. The management promptly complied.

Political correctness went out of the exit doors when Bachchan turned around in his swivel chair, his first appearance after the credit sequence, and shot a man because he ostensibly did not like his shoes. Everyone in the audience clapped and cheered as he, after the shooting, went on to fix a drink for himself and light up a cigarette. Of course, the real reason was that the man he shot had secret papers hidden in the heel of one shoe.

Nearly the entire chat between Bachchan’s Don and Helen’s Kamini, right after the song, Ye mera dil pyaar ka deewana – Bachchan deadpans the entire sequence – triggered giggles and cheers. And few could have heard the iconic lines – Don ka intezaar to gyarah mulkon ki police kar rahi hai… — in the midst of the all-around cheering and whistling.

Nobody seemed to mind when Don calls Zeenat Aman’s character, Roma, a jungli billi (wild cat) to show his appreciation of her fighting skills.

There was appreciation for some of Pran’s scenes and lines, especially when he mocks and chides Mac Mohan.

But what really brought the house down were two of the songs. Everyone clapped and whistled through the title track, Main hoon Don.

But that was just the appetizer. By the time Khai ke paan banaras wala came on, people could contain themselves no longer. They got up from their seats and began to dance in the open area in front of the screen.

It is the one song in Bachchan’s career where he totally lets himself go. Often dubbed someone who could not really dance, Bachchan moves with abandon and with none of the self-conscious aura he appeared to acquire in his later career. The audience matched him step for step.

It did not matter who you were, how old, and what your sensibilities were. For the duration of the song, and for much of the movie, there was Bachchan in all his glory and there were people showering him with all the unfettered adulation at their command.

Fourty-four years after first enthralling audiences all over the country, Don not only rekindled the spirit of Saharsa’s single screen in a Gurgaon multiplex, he also obliterated the segregation of Dress Circle and Upper Stall.

*This writer studied from Grades III to V at Jawahar Institution, Saharsa, which, much like some new-age schools of Gurgaon, did not have a prescribed uniform

[ad_2]

Source link